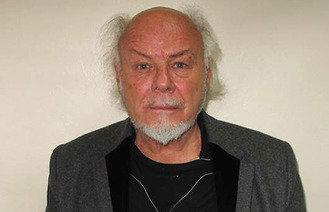

NewsMarch, 2 The Gary Glitter fans who still follow the leader

Steven Thomas was 37 years old when, as he puts it, “my world ended”. He had been a Gary Glitter fan since the early 70s: “Do You Wanna Touch Me on Top of the Pops, 1973, that was it. Bam. Totally hooked.” He had seen him live umpteen times, following him doggedly as Glitter clawed his way back from bankruptcy, from performances at shabby cabaret clubs in the late 70s, to college venues, to the huge venues he started filling in the 90s: Glitter’s final show, in 1997, was at Sheffield’s 7,500 capacity Motorpoint arena. Two years later, he was convicted of 54 offences of downloading child pornography and jailed for four months. “When he got done, when the convictions came along,” says Thomas, “I threw his autobiography in the bin, put my records in the attic.” Years later, however, he found himself idly typing Glitter’s name into YouTube. “And it all comes back. I saw there wasn’t that many videos on YouTube and I started uploading a couple of Gary Glitter tracks myself.” Perhaps understandably, not everyone was terribly enamoured of Thomas’s renewed interest in, arguably, one of the most reviled figures in British pop history. “I started getting a bit of shit,” he says. “A lot of my mates started getting a bit funny about things when they saw Gary Glitter videos on my Facebook page.” Teasing or threatening? “There’s a fine line, isn’t there?” he frowns. But he knew of at least one other Glitter fan who had been beaten up – “and he’s a big lad too” – so he decided to take action: deleting the videos and setting up another page under a pseudonym, where “all my friends are Glitter fans”. He sighs. “I believe music chooses you. The type of music, the artist, the song, it chooses you. It’s not your fault if you like it or not. And Gary Glitter’s music chose me.” Today, Thomas is part of an apparently burgeoning community of die-hard Glitter fans who congregate around a number of Facebook pages. One, called Gary Glitter’s Ganghouse, was set up in 2011 by 33-year-old Richard Smith, who discovered Glitter’s music long after the singer’s convictions: deeply improbable as it may seem, Gary Glitter is still apparently capable of attracting new fans. “Before that, one of my favourite artists was Jerry Lee Lewis, and obviously he’s a guy that comes with a reputation, he married his cousin and shot his bass player. And that never stopped me from appreciating his music. I knew what Gary Glitter had been convicted of. I don’t agree with that at all. Child abuse, child pornography, these are terrible things that people deserve to go to jail for. But that’s not a criticism of the music, the performance, the songs, or the production. “What really inspired me to start the page was that I knew this was music that really excited me, and I realised it was being omitted from history, written out of history. It’s not played on the radio, it’s not on glam compilation albums or box sets, there wasn’t a single picture of Gary in the glam exhibition at the Tate Liverpool. It’s treating the public like kids, really. You know, we’ll decide on your behalf what you can and can’t listen to. My attitude has always been, we’ll decide for ourselves, thanks very much.” The Gary Glitter’s Ganghouse Facebook page currently has nearly 7,000 likes. I stumbled across it while writing about one of the glam box sets Smith mentions: Universal’s lovingly assembled Oh Yes We Can Love. The compilers told me they had omitted Rock And Roll Part 2 and I Love You Love on the not-unreasonable grounds that the furore that including them might provoke would overshadow the whole project. I got in touch with the group because I was intrigued by this odd netherworld of fans who still refer to Glitter as “The Leader”, make their own Glitter calendars and T-shirts and arrange meetups to watch videos and discuss the old days, albeit clandestinely: “I think,” says Smith, “people are still concerned about going out in public and meeting up and going: ‘Hi everybody! Here for the Glitter fan convention?’” I was intrigued by what it was like to see your idol turn into a public hate figure before your eyes; how a continued, defiant love of Glitter’s music affected his fans’ lives; why anyone would want to expose themselves to the kind of abuse the page inevitably attracted, despite its assurances that it “celebrates the music … we do not condone his crimes”. “I mean, it’s not a constant barrage, but obviously I’ve seen people writing in saying, ‘Oh, if I ever find out where you live, you’re in for it’, so I know those threats are out there,” says Smith. “I’d be lying if I said it didn’t concern me. I have friends and family who don’t want to see me come to harm by meeting people who would be like: ‘You listen to Gary Glitter, you must be a fucking paedo.’ But that’s one of the reasons we’re putting ourselves out there, to chip away at that stigma.” To my surprise, fans were only too happy to talk, as long as their names are changed: “We want people to realise that we’re not these subterranean figures in basements with child porn,” says Smith, “we’re ordinary people, with families and marriages and children who like a bit of glam rock.” The only condition is that we don’t meet in public, which is how I’ve ended up in a Birmingham hotel room on a Saturday morning with six Gary Glitter fans reminiscing about their favourite gigs. All except Smith are middle-aged and followed Glitter before his convictions. Most describe having a moment not unlike when Thomas dumped his albums in the attic: “For a year or two, I was a bit kind of … because of my daughter,” says Mary Jackson, who works in social services, “obviously I’ve got my daughter, and you know …” But then they changed their minds. Most of them have come to the conclusion outlined by James Miller, a stocky debt collector from Yorkshire. He initially “didn’t want to believe” the charges against Glitter – “He was my hero” – but when he pleaded guilty to 54 counts of downloading internet pornography, “you sort of wonder and scratch your head, and then I thought, well I’ve made my distinction now, that was Paul Gadd, that was not my Gary Glitter.” But, occasionally, you get the queasy sense of people in denial of Glitter’s crimes. Jane Green is a fortysomething shop assistant who spent a significant proportion of her teenage years hanging around soundchecks and studios where Glitter was recording: “He was never anything other than a perfect gentleman.” She is the most outspoken of the group. It was she who made the Glitter calendars, she who “goes out all proud” around London in a Glitter T-shirt, she who last November opened a Twitter account, @leaderisback, with the name Gary Glitter, and ended up in the Sun and the Daily Mail. There is a moment when she starts talking, a little vaguely, about how Glitter has had “a really rough deal” from the legal system. She starts saying something else, about Glitter’s conviction in Vietnam, but Miller, perhaps realising how complaining about the rough deal meted out to a convicted paedophile is going to play with the wider world, interrupts: “You haven’t got long enough to talk about all that.” For all their jokes about how there was a stigma attached to being a Glitter fan even before the singer’s downfall, and assurances that most people are “fine” about their undying devotion, it’s clear their continued interest in Glitter has had some kind of negative impact on all their lives. Most have been sent threats via the internet. “I got one that went: ‘You work in social services, you must be sick, I’m telling your employer,’” says Jackson. “I just deleted it.” Occasionally the threats have spilled over into real life. “I would often get it off the smallest person in the room, because the smallest person’s the one who wants to take a dig at me,” says Miller. “I’ve had to walk away and not rise to it.” Green says she was called into work and told to remove a photo of her homemade Glitter calendar from her Facebook page. “I’ve had some people say to me, especially where I live now, in Gloucestershire: ‘You’d better watch what you say.’” So why do it? Why risk your job or your personal safety by taking a public stance about the music of a convicted paedophile? Why not just keep your memories and your music taste to yourself? The prosaic answer is that they genuinely love Glitter’s music and genuinely believe that if only they can convince others to listen to it, its undeniable brilliance will overwhelm any moral objections and then, as Smith puts it: “His music will be restored to its rightful place in history.” They trot out well-rehearsed arguments about other artists who have committed crimes yet still get played on the radio, about the impact and importance of Glitter’s music in the 70s – “Did you know he was the first artist in the history of the UK charts to debut with 11 consecutive Top 10 hits?” – about how Glitter can’t actually be profiting from his music in the way the tabloids suggest because he sold parts of his back catalogue years ago. But as they talk, another reason becomes obvious, which has less to do with Glitter’s music than with them. Whatever they say about being able to separate the man from the music, these are largely people whose memories of their youth have obviously been tarnished: “It’s not just wiping him out of history is it?” says Thomas at one point. “It’s us, they’re whitewashing us as well, we don’t exist any more. They’ve nicked 15, 20 years of my history.” “You can’t take a huge chunk of your life away,” nods Jackson. You get the feeling that they believe if they can somehow persuade the rest of the world, then those memories will regain their lustre. They grab at any scrap of information that suggests it might happen: the number of likes on the Facebook page, the fact that BBC4’s repeats of Top of the Pops didn’t excise a couple of Glitter performances from 1977, vaguely apocryphal-sounding stories about a DJ on Radio Solent who played Rock and Roll Part 2 on air and hosted a phone-in on whether Glitter’s music should be played. To hear Green tell it, the biggest danger facing someone who chooses to walk around London in a Gary Glitter T-shirt is that you might be trampled to death by fellow fans, eager to tell you that they think he should be back on the radio as well. But it isn’t going to happen. After I meet the die-hard fans, Glitter is charged with 10 child sex offences dating from the 70s and 80s: he is convicted of the attempted rape of an eight-year-old girl, four counts of indecent assault and having unlawful sex with a 12-year-old girl. In the wake of the conviction Green appears in the tabloids again. Her local newspaper got wind of her 2015 Gary Glitter calendar – “packed with sensational photos of The Leader” as her Facebook page puts it – and the Daily Mirror picks up on the story: the operations manager for the National Association for People Abused In Childhood claims that “for survivors of child sexual abuse these images could put them right back in that same emotional experience, reliving it”. The Ganghouse Facebook page stops being updated, as does its Twitter feed: one of the last messages dates from before the trial begins, encouraging fans to go to court and show their support. It turns out Smith is no longer running the Facebook page. It’s nothing to do with the court case, he says, but squabbling between different factions of die-hard Glitter fans over rarities and memorabilia: amazingly, it appears that people are fighting over who gets to curate a musical legacy that no one but them seems interested in. Miller is now in charge of Gary Glitter’s Ganghouse, and has decided to merge it with another Facebook group called Forever The Leader. When I speak to him, he sounds remarkably upbeat for a man whose idol will more than likely spend the rest of his life in prison. Likes on the Ganghouse page are going up again, he says, even though he’s not updating it. He claims that after “an initial few days”, the abuse has died down: “There’s not been as big a backlash as expected.” He insists the latest convictions don’t change anything: “Everybody that you met has the same thoughts. It’s about the music, the entertainer.” Nevertheless, he now concedes, Glitter’s music is never going to get back on the radio: “Even if the convictions were overturned, it’s not going to happen. There’s never, ever going to be acceptance.” Even so, “there’s still an awful lot of fans out there”, some of whom are apparently organising mass download campaigns to try to force Glitter’s music back into the charts. Of course people are going to criticise them, but they’re “mindless minorities”, people who believe everything they read in the Sun, online trolls. “Whatever good the internet has been,” he says, heavily, “it’s given the voice to some right idiots out there.” • All names have been changed.

Source: www.msn.com

March, 3

March, 3

March, 2

March, 2

February, 28 |

||

|

|

||